We visited this stunning chateau on the river Cher in August 2025, and all I’ve done since is read more about the very many little nuggets of fascinating history, and the lives of the extraordinary women that shaped the chateau into the place you can visit today.

Just 1 hour on the TGV from Paris, or 25 minutes from Tours, I don’t know why this wouldn’t be on everyone’s Paris visit itinerary. The station that serves the chateau is literally next to the ticket office and a short walk up the tree lined avenue brings you right to the Chateau’s front door.

It really is quite the sight. Incredibly evocative, and picture postcard pretty, there is a distinctly feminine softness to this chateau and its gardens, it feels less fortresslike and much more like a home. The more you learn, the more you begin to understand why this is so.

Katherine Briconnet (1494-1526) is our first lady of note. As the wife of the chateau’s master, Thomas Briconnet, Katherine was instrumental in its construction and design during the early 16th century.

Under her guidance, the chateau was transformed into an architectural marvel that blended Gothic and Renaissance styles. Katherine’s vision included not only the impressive structure but also the surrounding gardens, which became famed for their beauty. She commissioned renowned artists and craftsmen to contribute to the chateau, ensuring it reflected both style and elegance.

Her legacy is not just in the physical aspects of the chateau but also in the cultural vitality she fostered there. Katherine hosted numerous gatherings of artists and intellectuals, which contributed to the chateau’s status as a center of Renaissance culture. Her attention to detail in both the interior design and the gardens revealed a distinctly feminine touch, creating a hospitable and warm environment.

Katherine Briconnet’s influence laid the groundwork for Chenonceau’s continued significance throughout history, evolving into a symbol of female power and creativity, further marked by the many women who followed her in the chateau’s stewardship.

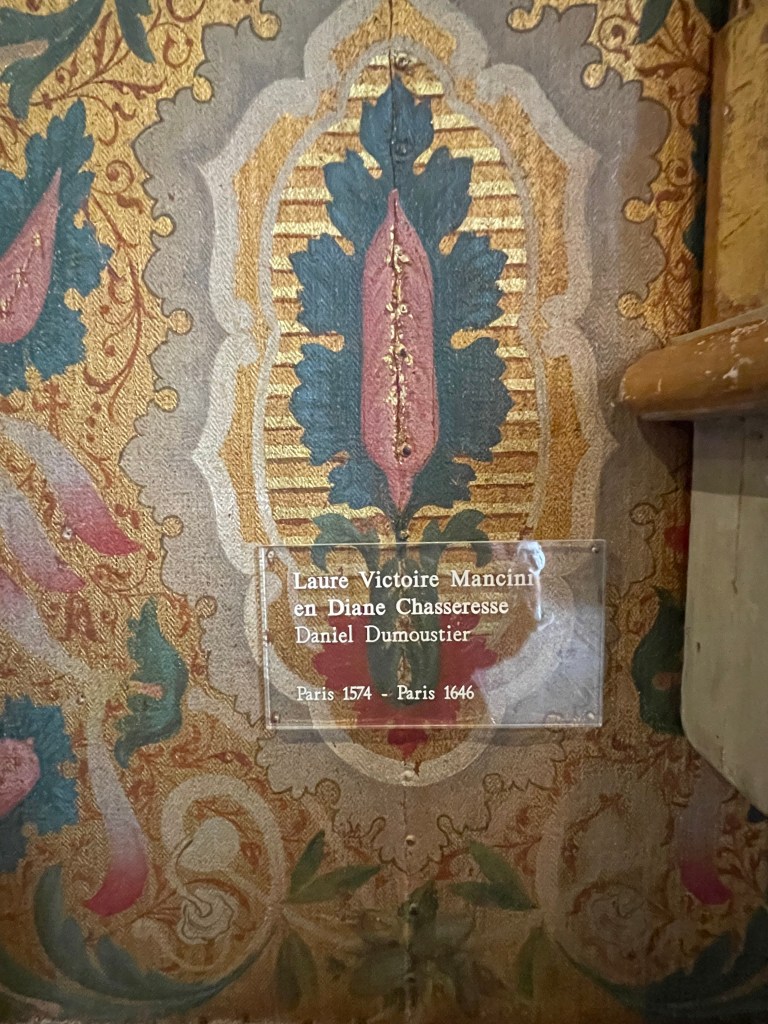

Diane de Poitiers (1499-1566) became the Chateau’s proprietress in the 16th century. As a renowned beauty and the long-time mistress of King Henry II of France, Diane’s influence significantly transformed the chateau and its surrounding gardens.

Upon her acquisition of the chateau in 1547, a gift from the king, Diane embarked on extensive renovations and enhancements. She is credited with the creation of the exquisite gardens that are still admired today. Under her direction, the gardens flourished with intricate designs, and showcased a blend of French formal and more relaxed botanical styles.

Diane de Poitiers held a great deal of social and political power, and, even after her death, the impact of her stewardship continued to resonate within the walls of Chenonceau, as the baton then passes to our next extraordinary woman.

Catherine de Medici (1519-1589) played a pivotal role in the history of Château de Chenonceau, particularly after the death of her husband, King Henry II. Following his passing, Catherine removed Diane (as you would), and became the owner of the chateau and used it as a strategic political and cultural platform during a tumultuous time in French history.

Catherine was adept at using Château de Chenonceau for political maneuvering. She hosted numerous influential figures at the chateau, fostering relationships and alliances that were crucial during the religious wars in France. Her adeptness in court politics and her role as a mother to several kings and queens solidified her influence and presence in French history. 3 of Catherine’s 10 children went on to become Kings of France, including Francis II who went on to marry Mary Queen of Scots, and Henry III who went on the marry Louise of Lorraine, our next significant chatelaine.

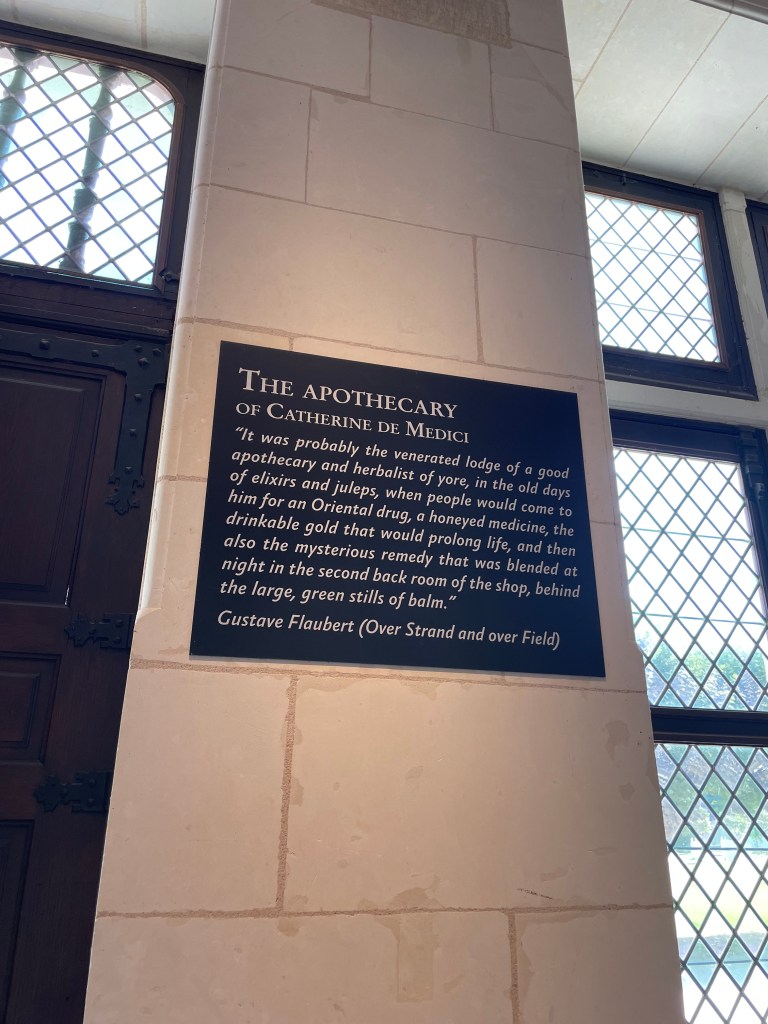

A special mention and photo gallery here for the astonishing apothecary of Catherine de Medici. I want it, I need it, it has to be mine. I have a few old apothecary bottles and chemist jars in my possession, but this is the stuff of absolute dreams. I adore it.

Louise of Lorraine (1553-1601) As the wife of King Henry III of France, Louise became the Queen of France and played a significant role during her husband’s reign, especially during the Wars of Religion.

After the assassination of Henry III in 1589, Louise was engulfed in grief and chose to withdraw from the public eye, adopting a life of mourning, wearing only white as was the courtly custom, and earning herself the name “The White Queen”. She lived in Chenonceau, where she sought solace amid its beauty and to escape the turbulence of the political environment.

During her time at Chenonceau, Louise transformed the chateau into a personal sanctuary, marked by her profound sadness over the loss of her husband. It’s palpable when you enter her bedchamber, painted in black and curtains closed. For all its sombre decoration, theres something very beautiful about this space to me. Perhaps it’s my little gothic heart.

Her death marked the end of a royal presence at the chateau.

Louise Dupin (1706-1799) was a pivotal figure in the history of Château de Chenonceau, particularly during the 18th century, and I think she is my absolute favourite. As a prominent intellectual and salonnière, she inherited Château de Chenonceau from her husband, who passed away in 1738. She dedicated herself to the upkeep and revival of the property, ensuring that it remained a place of beauty and cultural significance.

In her time, Louise Dupin hosted a variety of salons, inviting artists, writers, philosophers, and other intellectuals to discuss ideas and exchange knowledge, and connections with influential figures of the age (such as Voltaire, who named her “the goddess of beauty and music”), helped to create a network that would further solidify the chateau’s status as a centre of cultural exchange.

Louise Dupin was an ardent advocate for gender equality, and was arguably centuries ahead of her time. Her major, though unfinished, work, Ouvrage sur les femmes, calls out the sexist bias of ancient and contemporary scientists and historians. She argues that women are intellectual and moral equals to men, and that their continued subjugation and repression, denial of education and loss of rights at marriage amongst other things, are orchestrated by men to protect their own interests.

She cunningly managed to protect the chateau from the revolution, she even turned the chapel into a wood store to shield it’s religious use from those that would look to destroy it.

Apolline, Countess of Villeneuve (1776-1862) In 1799, Apolline de Guibert married the Count of Villeneuve, the heir to Chenonceau through his great-aunt Louise Dupin. They devoted themselves to restoring it to its former glory, with restoration of the monument and reconstruction of the gardens. The Countess, passionate about botany, planted the plane trees of the famous Grande Allée, restored the Green Garden and reintroduced white mulberry trees. These trees hold a significant place in the history of silk production, which played an essential role in the economic landscape of France during the Renaissance and beyond.

The cultivation of mulberry trees was crucial because their leaves serve as the primary food source for silkworms, an essential aspect of silk production. This connection highlights the intertwining of nature and commerce, as the chateau’s gardens were designed not only for aesthetic enjoyment but also to support the economic activities of the time.

Marguerite Wilson Pelouze (1836 – 1902) In 1864 she purchased the chateau for the sum of 850,000 francs, and Marguerite, a child of the industrial bourgeois, decided to turn the monument and her park into a theatre of her sumptuous tastes. In her Academy of Arts and Letters, she welcomed writers, historians, musicians, painters and sculptors. A young Claude Debussy spends a summer at the chateau and is quite dazzled by the refinement of his surroundings, and their owner. She spent a fortune on restoring the estate for it to resemble the way it was at the time of Diane de Poitiers but eventually much talk of political (and amorous) scandal caused her ruin. Chenonceau was then sold in 1888, and passed, (via Credit Foncier), into the Menier chocolate family who remain the owners to this day.

Simone Menier (1881-1972), a prominent figure in the history of Château de Chenonceau, played a critical role in its preservation during the 20th century. She was the granddaughter of the renowned French chocolatier and industrialist, Eugène Menier, who had acquired the chateau in 1913.

Under her stewardship, Simone Menier dedicated herself to restoring and maintaining the château, which had fallen into disrepair during the years before her family’s ownership. Her efforts included restoring the gardens, enhancing the interior decorations, and preserving the rich historical artifacts within the chateau.

Simone also opened Château de Chenonceau to the public, providing access for visitors to appreciate its beauty and historical significance. Her commitment not only preserved the chateau’s legacy but also ensured its status as a major cultural and tourist landmark in France. Through her dedication and vision, Simone Menier played an essential role in safeguarding the history and charm of Chenonceau for future generations.

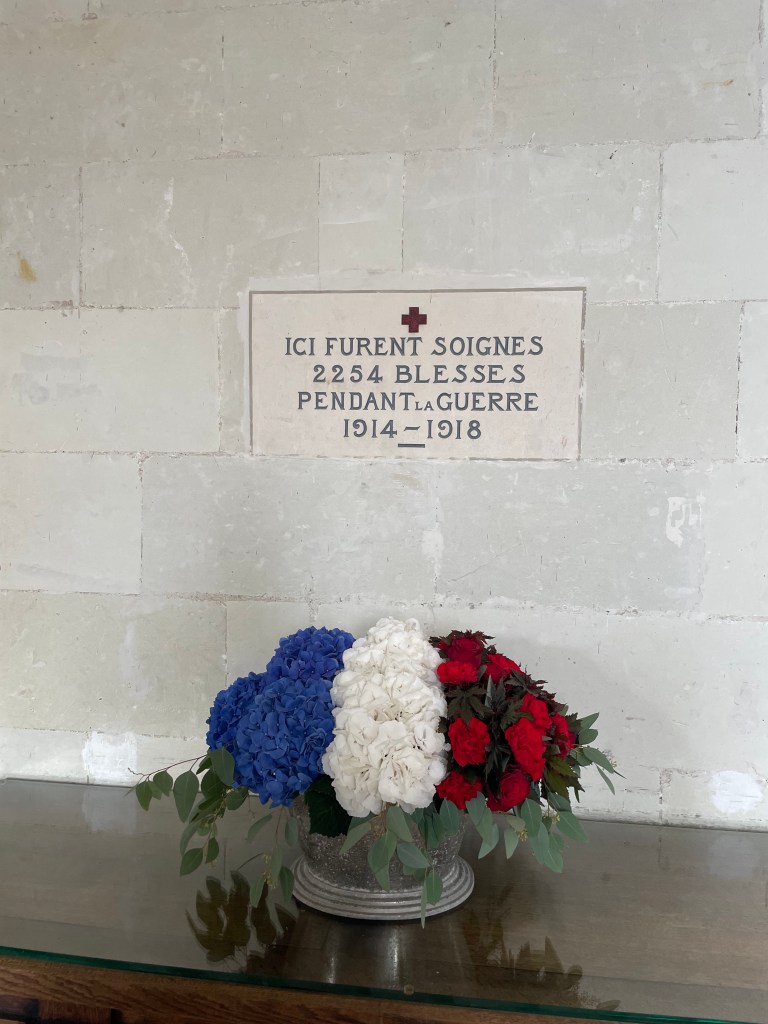

In WWI the great gallery and indeed the wider chateau, was used as a military hospital. Can you imagine returning from the horrors of life in the trenches to convalesce here? A plaque states that 2254 injured people were cared for here during this time. A simple red white and blue flower arrangement sits beneath in their honour.

Château de Chenonceau also played a notable role during World War II. The chateau’s unique position, spanning the River Cher, provided both a physical and symbolic bridge between the regions controlled by the occupying forces and those under Free French or Resistance influence. The picturesque setting and its extensive gardens created a deceptive atmosphere, allowing covert activities to unfold without drawing attention.

Members of the French Resistance used the chateau as a place for meetings and as a safe house for fugitives. Its labyrinth of rooms and concealed passages made it an ideal location for hiding individuals who were sought after by the German authorities. The surrounding forest provided further cover for clandestine operations, with Resistance fighters using the estate to plan their manoeuvres and coordinate efforts against the occupiers.

As a visitor, it’s hard not to make comparisons to Versailles, and on sheer size and grandeur alone, Versailles probably wins, although I have the softest of spots for the Queen’s Trianon estate over the golden clad extravagance of the palace. Here at Chenonceau though, the atmosphere feels a little different. Instead of the “look how powerful and wealthy I am” golden flashiness of Versailles (current Oval Office anyone?), it’s more, see how refined and elegant and intelligent and of good taste I am. It’s less flashy, (although no less impressive for it), it feels like an authentic representation of the things that a group of extraordinary women genuinely had passion for, and wanted to surround themselves with. Botany, science, beauty, grace, the love for their children, even grief. Theres a warmth and a vulnerability, and perhaps less of a need to try quite so hard. It feels like those women are letting us really see them, what a privilege that is.

I loved this place. I have a mountain of reading still to do, there are some suggestions to links with The Man in the Iron Mask, and I have fallen down another rabbit hole there. I won’t write about that here because it’s a mystery, wrapped in a fable, and possibly a little more modern recent detective work that might pour cold water on some of the things we thought we knew. Maybe there’s a future blog in that all by itself.

I hope you enjoyed what is quite a long read for one of my usual blogs, but, like all aspects of French History, I found it such an interesting thing to learn about. I will especially never tire of reading about extraordinary women doing extraordinary things and I will lament that I hadn’t previously heard of some of them. It seems Louise Dupin is still sadly right about quite a lot.

Thanks for reading.

V x

Please subscribe for more ideas for great France (and beyond) days out and little daily snapshots of a life in Rural France.

It’s a glorious place

LikeLiked by 1 person

Isn’t it just.

LikeLiked by 1 person